Supersets, Mega-Sets and Monster-Sets

Another concept related to our exercise progression is the concepts of supersets. Because many injuries and performance issues are the result of muscular fatigue, we have incorporated the use of super setting into this program. A superset is simply moving directly from one exercise to the next without rest in between sets. This increases the physical, including strength, endurance and cardiovascular, demands of the exercise routine which can result in improved endurance and power output, especially at the later stages of activity in sports, i.e., “later in the game.” A progression of the superset concept is the mega-set and the monster-set. These concepts will be incorporated throughout the Corrective Exercise Program, and we will use the following definitions:

- Superset –

move right from one exercise to the next.

Superset in our program includes only 2 exercises. The first exercise is performed and then

followed immediately by the next exercise without a rest. Following completion of the second

exercise, rest.

- Mega-set – refers to moving right from one exercise to another exercise to a third exercise without any rest in between. Once the third exercise is complete, then the athlete should rest for a sufficient amount of time in order to return to 70% of resting heart rate.

- Monster-set --

the most difficult of the three.

This is the combination of more than 3 exercises. Once the final exercise is complete,

then the athlete should rest for sufficient amount of time in order to

allow a return to 70% of resting heart rate.

This type of training methodology can be used in many ways, but some common uses include:

- To target a specific muscle. When working on endurance of an isolated muscle it is good to combine exercises that focus on that muscle. One common example of this is the use of side stepping and retro monster walks in a superset fashion. These two exercises focus on gluteus medius strength and endurance, but require the muscle to work in different ways.

- Pre-fatigue of accessory muscles. If you are attempting to work on maintaining proper kinematics in the final stages of a hip abduction exercise, and are having a lot of gluteus maximus involvement toward the end of the routine, you could superset a gluteus maximus focused exercise to pre-fatigue the gluteus maximus, then follow with a gluteus medius targeted exercise.

- For endurance of the entire kinetic chain. Monster-sets are great for working the entire kinetic chain. An example of this is a monster-set of jump squats, with SEBT (star excursion balance test), side-stepping and then abdominals on a stability ball.

Don't be afraid to put your hands on the athlete. The best training mode or apparatus is the hands of a skilled clinician. One technique we employ throughout training is the use of manual resistance or manual perturbations at the end of a sequence of exercises. Use of manual resistance or resistance with perturbations by a skilled clinician is invaluable. This allows you to maximize training benefit by pushing the athlete to the next step while maintaining proper form and technique. Simply grading our resistance allows us to emphasize maintaining proper positioning while continually fatiguing the stabilizers.

Don't be afraid to put your hands on the athlete. The best training mode or apparatus is the hands of a skilled clinician. One technique we employ throughout training is the use of manual resistance or manual perturbations at the end of a sequence of exercises. Use of manual resistance or resistance with perturbations by a skilled clinician is invaluable. This allows you to maximize training benefit by pushing the athlete to the next step while maintaining proper form and technique. Simply grading our resistance allows us to emphasize maintaining proper positioning while continually fatiguing the stabilizers.

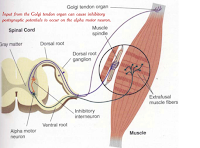

Concept of Pre-Stretch (Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation)

From anatomy, exercise physiology

and motor learning, we know that if we provide a rapid stretch to a muscle, a

stretch to the muscle spindle results.

If the stretch to the muscle spindle is followed by an immediate

forceful contraction, the muscle can produce more force than By producing more

force, you are able to work the muscle more because you are involving more of

the muscle fibers than you would if you just contracted from a resting state. This allows us to increase work the muscle

does which results in improved power and performance over time.

From anatomy, exercise physiology

and motor learning, we know that if we provide a rapid stretch to a muscle, a

stretch to the muscle spindle results.

If the stretch to the muscle spindle is followed by an immediate

forceful contraction, the muscle can produce more force than By producing more

force, you are able to work the muscle more because you are involving more of

the muscle fibers than you would if you just contracted from a resting state. This allows us to increase work the muscle

does which results in improved power and performance over time. if just contracted from the rested state.

This is the same concept used in plyometric strength training (box jumps, jump training, etc.—see the next section) and it has been utilized in performance training protocols for decades. We use this same concept throughout our training program in order to push the physical demands of the program and to force larger gains in strength and power.

However, where most training programs fail with this concept is allowing too much time to elapse between the stretch and the contraction. Like repetitions to substitution, as the athlete fatigues, he/she will begin to allow more and more time to pass between the stretch and the contraction. When this happens, the kinetic energy that is stored with the rapid stretch is lost and therefore the athlete is not able to get maximal muscle contraction when force is exerted. The key then is to have a forceful contraction immediately following the stretch. It is important to keep an eye on the athlete as fatigue sets in, and, much like repetitions to substitution, stop or rest when the time between the stretch and the contraction increases.

Plyometrics

Plyometrics is a training medium we can use with athletes that raises the intensity of the exercise and one that has a high carry over to sport. Plyometrics incorporates the concept of pre-stretch or proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation described in the previous section. However, caution must be used in employing plyometrics in a training program because these types of exercises, when applied incorrectly, can add to or even cause certain kinds of musculoskeletal injuries. Some of the most common injuries seen with plyometics are:

- Ankle

sprains/strains

- Shin

splints

- Patellar

tendonitis

- Meniscal

injuries

- ACL

injuries

- Low

back/SI pain

- Muscle

pulls/strains

- Plyometrics

should not be used more than 2 times in a training week – using more

than 2 times a week can result in overuse injuries like shin splints.

- Plyometrics

should never follow a heavy training day – performing plyometrics

after an unusually hard practice or training session the day before can

lead to over training and muscle strains/sprains.

- Plyometrics

should always be employed at the beginning of the training session and

not at the conclusion – using at the end of a training session results in

poor performance and technique which can lead to ACL, meniscal and other

types of injuries.

- The

concept of repetitions to substitution should be strictly adhered to

when using plyometrics – this has a HIGH specificity to sports and therefore

training with bad technique results in carryover of bad technique to

sport.

- A plyometric

routine should follow a standardized progression without skipping one

phase and jumping to the next – this can avoid 90% of the injuries

resulting from this type of training.

Increased Intensity = Improved Performance

Keeping this concept in mind does not mean that raising the intensity always equates to improved performance. Take the following case as an example. This young athlete was prescribed plyometrics for 4 weeks under the supervision of her treating clinician and strength coach. I suspect that any of us seeing this would argue that we would never let this happen to our athlete. YET, it happens everyday. When exercising in group settings with little supervision or when high level training methodology supervision is delegated to less skilled individuals. This type of technique does not and will not lead to improved performance. Rather, she has paid us to train her to poorer performance and increased risk for injury.

Once technique and stability are mastered, it is appropriate to move to the next level. Never skip a level until this has been assessed. Many programs claim to improve athletic performance. What we have attempted to do is combine the research from all of the related sciences (neurology, exercise physiology, and biomechanics) to bring you unique concepts not found with many of the current prevention programs. Our goal is to allow you to progressively, systematically and safely progress your program to the next level. In order to continually progress strength/endurance, to improve movement patterns and to improve athletic performance, you must constantly challenge the body. By following the above concepts, you will be able to safely take the athlete to the next step while challenging their entire neurological, physiological and musculoskeletal system.

No comments:

Post a Comment