For increased sensitivity, scoring of each repetition is ideal but time consuming.

TEST #2: Single Leg Squat Test ( SLST) - The SL Squat (SLST) test assesses the athlete’s ability to perform a partial squatting motion on one leg. Due to the fact that so much athletic activity involves single limb activity, this is a crucial test and will provide you with an idea of the athlete’s ability to stabilize his or her extremities while in motion. This will provide a great deal of insight into potential weaknesses, tightnesses and where the athlete’s limitations are with regard to the lower extremity activities. Performance on this test can be directly linked in particular to power generation in the lower body.

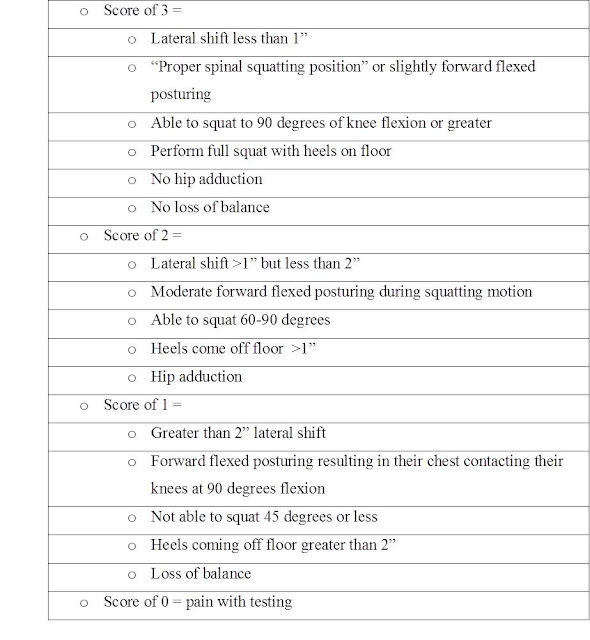

During this test, the subject stands on one leg while the other leg is bent to between 45-90 degrees. The subject is asked to squat down to 45° and repeat the motion 10 times. Once the subject completes 10 repetitions, he/she is then asked to perform the same test on the opposite side for 10 repetitions. During this test, you are assessing the ability to perform the test, whether there is excessive lumbar flexion vs. knee flexion, whether there is a variance between the right and left sides, if there is adduction/internal rotation at the hip or knee and if the subject is able to stay balanced during the course of the examination.

Clinical Implications of the 45° Single Leg Squat Test

There are numerous deviations that show up in athletes performing 45° SL Squat Test. Below is a list of some of the most common deviations associated with the 45° SL Squat Test and the associated clinical implications.

Hip adduction and internal

rotation with ascent/descent or trendelenburg – As above, these three

movements are combined together due to the fact that they are so often

associated with one another. In this

test, these deviations can become even more apparent. If weaknesses exist, they often appear when

the athlete attempts this test first with a notable drop in the pelvis

(trendelenburg), followed by an accompanying adduction at the hip with internal

rotation of the femur. In this example,

the subject has a slight trendelenburg at the hip along with significant

adduction at the hip with slight internal rotation at the femur. The combination of these motions occur

secondary to poor core stability, and/or poor gluteus medius strength or

endurance.

Hip adduction and internal

rotation with ascent/descent or trendelenburg – As above, these three

movements are combined together due to the fact that they are so often

associated with one another. In this

test, these deviations can become even more apparent. If weaknesses exist, they often appear when

the athlete attempts this test first with a notable drop in the pelvis

(trendelenburg), followed by an accompanying adduction at the hip with internal

rotation of the femur. In this example,

the subject has a slight trendelenburg at the hip along with significant

adduction at the hip with slight internal rotation at the femur. The combination of these motions occur

secondary to poor core stability, and/or poor gluteus medius strength or

endurance. Suggested Corrective Exercise: These individuals respond well to core strengthening and gluteus medius strengthening (PNF step-up/side-stepping series).

Trendelenburg/Cork screwing – if there is weakness in the hip, this will often become more pronounced in a single leg stance position. Most often, this will present itself as a trendelenburg (as described above). If the weakness in the hip is significant enough, then there may be a loss of control at the hip resulting in a “cork screwing” motion.

In this particular example, the subject starts to “cork screw” at the hip, resulting in significant side bending in the lumbar spine and eventually loss of balance.

Suggested Corrective Exercise: Due to the extent of weakness of the hip and core, these subjects do remarkably well with isolated strengthening and endurance exercise training for the gluteus medius and the core as well as a proprioceptive retraining program.

Asymmetry – as the force

demands increase for the entire lower kinetic chain with this test, bilateral asymmetries

become more apparent. Using the example

from above, we can see when we compare the subject’s left leg to his right,

that there are notable asymmetries. If these are left unchecked this leads to

increased potential for injury on both legs.

Asymmetry – as the force

demands increase for the entire lower kinetic chain with this test, bilateral asymmetries

become more apparent. Using the example

from above, we can see when we compare the subject’s left leg to his right,

that there are notable asymmetries. If these are left unchecked this leads to

increased potential for injury on both legs.

Asymmetries can present

themselves in several ways. This

includes but is not limited to:

- Variance

in ability to perform

- Decreased

number of repetitions able to perform on right vs. left

- Variance

in concentric strength – variance in difficulty with ascent right vs.

left. This is most notable with

inability to obtain full knee extension on right vs. left.

- Variance

in eccentric strength – variance in difficulty with descent right vs. left. You will most often see the subject

compensate with decreasing the range of motion they will descend to on

one side vs. the other.

- Variance

in hip strength – resulting in a trendelenburg or cork screwing on side

vs. other

- Difference in hip or ankle range of motion or range to which the athlete is able to descend or ascend.

Asymmetries of this nature can

result from poor balance, weakness or lack of stability of the proximal hip or

poor proprioception.

Suggested Corrective Exercise: These athletes do well with single leg training protocols (single leg press, single leg squats, and single leg functional activities).

Inability to perform – if an athlete is simply not able to perform the squat or if he/she is not able to perform without losing balance. If they are unable to complete the test as a result of weakness, then a closer assessment of the squat should be performed, looking for lateral shift in particular.

Suggested Corrective Exercise: If there is significant lateral shift, these subjects respond well to the squatting protocol (squat pause protocol, rapid squats, rotational lunges). If the inability to perform this test is a result of loss of balance, then these athletes respond well to the Single Leg with Dynamic Lower Extremity Movement exercise progression.

No comments:

Post a Comment