Did you know:

- More than 75 percent of runners experience at least one overuse injury during training (Egermann et al. Int J Sport Med 2003). T

- The majority of running injuries, more than 90 percent, occur in the lower kinetic chain (Cipriani et al J Ortho Sport Phy Ther 1998)

- In runners, the knee is the most injured body part (Van Gent et al Br J Sports Med 2007).

- 49% of runners report an injury in just the last year of training (Hauret et al Am J Sports Med 2016)

- The risk for these injuries increases as runners increase their training mileage (Burns et al. J Orth Sport Phy Ther 2003).

- The majority of all running injuries are non-contact in orientation (no traumatic impact, fall or collision) and are considered preventable (Hauret et al Am J Sport Med 2016).

We know from the research that non-contact injuries can result from predictable movement patterns or altered biomechanics. Altered biomechanics (valgus collapse) have been shown to cause knee injuries (Hewett et al Am J Sport Med 2017) that are often associated with running. These same movement patterns are associated with all non-contact lower limb injuries often seen in runners, including trochanteric bursitis, patellofemoral pain, iliotibial band friction syndrome (ITBFS) and plantar fasciitis. In addition, the same movements associated with risk are the same movement patterns that add to decreases in speed and running economy (Myers et al J Strength Cond Res 2005). Studies have shown a correlation between these altered biomechanics and impacts on running gait and injury risk. Asymmetrical hip strength has been shown to add to decreased hip extension at toe-off, increased adduction (knocking knees) and pronation at midstance as well as increased risk for ITBFS (Noehren et al J Ortho Sport Phy 2014).

We know from the research that non-contact injuries can result from predictable movement patterns or altered biomechanics. Altered biomechanics (valgus collapse) have been shown to cause knee injuries (Hewett et al Am J Sport Med 2017) that are often associated with running. These same movement patterns are associated with all non-contact lower limb injuries often seen in runners, including trochanteric bursitis, patellofemoral pain, iliotibial band friction syndrome (ITBFS) and plantar fasciitis. In addition, the same movements associated with risk are the same movement patterns that add to decreases in speed and running economy (Myers et al J Strength Cond Res 2005). Studies have shown a correlation between these altered biomechanics and impacts on running gait and injury risk. Asymmetrical hip strength has been shown to add to decreased hip extension at toe-off, increased adduction (knocking knees) and pronation at midstance as well as increased risk for ITBFS (Noehren et al J Ortho Sport Phy 2014).

With knee injuries injuries being so common among runners, this has led to a catch all diagnosis category called "Runner's Knee". So what is runner's knee and what can we do to prevent it. Recently I was asked to contribute to a running article on runners knee. As such, this spawned me to take a deeper dive in this series to really look at this in depth and see what we can do from a prevention standpoint.

No matter how you define runners knee (patellar tendonitis, IT

band friction syndrome, patellafemoral pain syndrome, etc), what the research shows us is that >80% of these are non-contact in orientation. As such, there is usually a root cause or something else that is leading to the “runner’s knee”. Therefore to address what we can do to

prevent, we first have to look at some common “root” causes of runner’s

knee. Keeping in mind this is not an

exhaustive list, it includes only some of the most common “root” causes.

- Shoes – poor shoes or being fit with the wrong shoe can significantly alter force attenuation (how force is absorbed by your body) during running. Absorbing shock (or force) is vital to preventing shin splints, lower extremity injuries and runner’s knee. Several problems with shoes can add to your problem. Some common issues include; damp shoes, worn out shoes, wrong kind of shoe.

- Damp Shoes - One thing that can add to a decrease in shock absorption is damp shoes. With increase in dampness of the shoe comes less shock absorption which can add to increase stress to the foot/ankle and knee. We often suggest having two pairs of running shoes so that you can dry one out while alternating to another pair of shoes. So, let them dry out!

- Worn out shoes - Another problem we see with shoes is runners will use the same pair for a year or two. With time and increase in mileage, the shoes begin to wear down and they lose some of their elastic properties which results in less shock absorption. This means that more of the ground reaction force at heal strike and midstance is absorbed at the foot and ankle and then at the knee. Running shoe manufactures vary on their recommendations but most will tell you that you should replace your running shoes anywhere from every 300 to 500 miles. The more miles you put on the shoe, the less elastic recoil the shoe has which can add to increase in potential for overuse injury. So, replace worn out shoes!

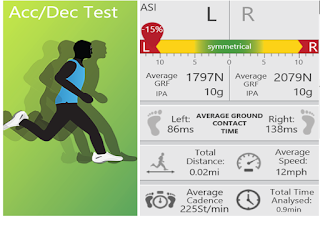

- Wrong Shoe - Finally, another issue that we see with shoes is being fit with the wrong shoe. We will often see athletes that are told they pronate or supinate and then are put in a shoe to control for that. All too often, we will see runner put in a shoe that is supposed to control that when in fact the pronation or supination that occurs does not in fact necessitate a shoe to control. So, you have a runner who has been running comfortably with over pronation, but not pathological pronation, and you suddenly change that. But, you are not only changing that at the foot but the entire lower kinetic chain mechanics are then changed. What we typically do when we assist a runner in choosing a shoe, we typically do a running assessment. Using a 3D wearable sensor (DorsaVi), we can have the athlete run in three different types of shoes. This system will provide us with biomechanical data for right and left IPA (initial peak acceleration – how well you control the foot into the ground), right and left ground reaction force at midstance and stance time on the right and left. This allows us to directly see how well they are controlling the forces through the lower limb and which shoe provides them with the optimal performance and force attenuation. So, make sure you are picking the right shoe! It is the first contact point in the kinetic chain.

We hope you enjoyed this discussion and as we continue next week we will start to look at faulty running mechanics and how this can add to runners knee. If you would like to find out more about how to get a 3D running assessment near you, contact us @ acl@selectmedical.com. Stay tuned and please share with others you think might be interested. #ViPerformAMI #DorsaVi #RunSafe

Dr. Nessler is a practicing physical therapist with over 20 years sports medicine clinical experience and a nationally recognized expert in the area of athletic movement assessment and ACL injury prevention. He is the founder | developer of the ViPerform AMI, the ACL Play It Safe Program, Run Safe Program and author of a college textbook on this subject. Trent has performed >5000 athletic movement assessments in the US and abroad. He serves as the National Director of Sports Medicine Innovation for Select Medical, is Vice Chairman of Medical Services for USA Obstacle Racing and movement consultant for numerous colleges and professional teams. Trent is also a competitive athlete in Brazilian Jiu Jitsu.

No comments:

Post a Comment