Stretching and Flexibility

Stretching and flexibility are often areas neglected by many athletes, especially working ones, since often training time is limited already. However, for every hour invested, stretching activities may in fact pay the biggest dividends of all training activities. It is important for your athletes to spend time every day stretching and working on flexibility. For many sports, commitment to increasing flexibility can result in “free speed” by improving posture, position and aerodynamics in sports such as cycling and almost all others. Also, by increasing flexibility through a regular stretching routine, many injuries can be avoided.

During exercise, and most activities of daily living, muscles and connective tissue are shortened and tightened over time. Rarely do we require our muscles to go through the full range of motion they are capable of during sports activities, or even during other kinds of activities. Instead, during sports we simply contract the muscles over and over, in the same ways, and so eventually they tighten and lose the ability to lengthen to full capacity. This can not only limit performance through limited power output and poor positioning, but also can increase the likelihood of injury, because tight muscles that are asked to perform rapid or extensive motion without adequate flexibility can be subject to tearing and trauma that would otherwise not occur.

Let’s look at swimming as an example. In order to get a full, long arm stroke and maximum reach during each rotation of the shoulder, the muscles of the shoulder and upper back must be flexible. This allows the arm to fully extend, the body to roll to the side and balance in the streamlined position momentarily, while the forearm rotates in and down vertically during the catch phase of the stroke. The shoulder then brings the forearm in toward the body allowing the pulling motion to extend the hand and arm past the hip during a rolling motion of the core at the finish. Also, during swimming, it is critical that the ankles be loose and flexible enough to allow complete plantar flexion, creating a straight line extending down from the shin over the top of the foot during the kick, which decreases drag through the water. The importance of this cannot be overemphasized, as drag is the number one limiter in swimming efficiency and speed.

Another example where we see great

benefit in having elastic muscles is in cycling. Tight hamstrings on the bike limit the

extension of the leg down stroke during pedaling, prevent full range of motion

on the second half of the pedal stroke, and minimize power output. Hamstrings that are tight effectively prevent

the leg from straightening, which ends up reducing power output generated in the

core, and transmitted via the extension of the hip and knee at the bottom of

the pedal stroke. Often cyclists will

lower their seat to counteract tight hamstrings, but since this further prevents

adequate straightening of the leg as the hip flexor and knee propel the leg

forward and the quadriceps pushes the foot downward, power is further reduced. In turn, tight hamstrings put more pressure

on the lower back, requiring the rider to contract the lower back in response

with every pedal stroke, particularly when riding in the aerodynamic position

in pursuit or aero bars.

Another example where we see great

benefit in having elastic muscles is in cycling. Tight hamstrings on the bike limit the

extension of the leg down stroke during pedaling, prevent full range of motion

on the second half of the pedal stroke, and minimize power output. Hamstrings that are tight effectively prevent

the leg from straightening, which ends up reducing power output generated in the

core, and transmitted via the extension of the hip and knee at the bottom of

the pedal stroke. Often cyclists will

lower their seat to counteract tight hamstrings, but since this further prevents

adequate straightening of the leg as the hip flexor and knee propel the leg

forward and the quadriceps pushes the foot downward, power is further reduced. In turn, tight hamstrings put more pressure

on the lower back, requiring the rider to contract the lower back in response

with every pedal stroke, particularly when riding in the aerodynamic position

in pursuit or aero bars. An effect of tight hamstrings can also be seen in running mechanics when the hamstrings effectively produce a “stopping” motion during the roll and propulsion of the body forward after the toe off. To look at running in more depth, it is easy to see that flexible quadriceps and hip flexors allow the leg to swing more freely on its axis and allows greater extension of the forward foot and leg, as well as greater recovery of the leg behind the center of gravity as the runner moves forward. In addition to limiting the range of motion of the lower body during running, tightness in the hamstrings, hip flexors, gastrocnemius, and quadriceps limits the capacity of the runner to use gravity to catapult the body forward. Tight lower extremity muscles can contribute to a kind of “braking” effect during forward propulsion. The athlete is not then able to use eccentric loading and the resulting “elasticity” of his or her body weight against ground forces to his or her advantage. This means the athlete has to expend more energy to travel the same distance at the same rate of speed.

Although the benefits of stretching are not agreed upon in the athletic or scientific communities, it does appear that stretching can decrease the likelihood of injury and speed recovery in some cases. If we assume there are some benefits to stretching and after looking at several sport specific examples that further reinforce the need for regular stretching, let’s explore a few stretching styles. There are many, but for the purpose of this blog, we will address: ballistic, static, contract - relax, active isolated stretching (AIS), dynamic stretching and yoga.

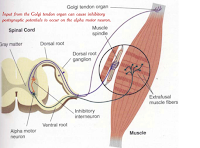

Ballistic stretching involves bouncing repeatedly to try to loosen the muscle. It has been found that this actually tightens the muscles due to repeated contractions, which can actually lead to injury, and so is not a recommended method for stretching. Stretching in this fashion initiates a response by the muscle spindle to contract which has the net result of a contraction of the muscle which further resist stretching.

Static stretching involves stretching the muscle to the point of slight discomfort (not pain) and then holding the position for a minimum of 20-30 seconds in order to allow the muscle to “release” and consequently loosen and relax. This is probably the most popular form of stretching today. It is important to avoid static stretching before a warm up or workout, when the muscles are cold. Static stretching is best done at the end of workouts, or at least after a thorough and adequate warm up of the muscle groups involved. When static stretching is applied with the literature, we can find even more dramatic results. In a study by LaStayo et al published in 1994 in the Journal of Hand Therapy, the authors found that static stretches held for a sustained period of time (15 min or greater) resulted in greater plastic changes in collegian tissue. This equated to longer lasting length changes than traditional stretching. The concept TERT (total end range time) has been applied since then in sports medicine centers around the US. When the concept of TERT is applied with moist heat (moist hot pack) or deep thermal heat (US), then the impact is even greater.

Proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF) was discussed in more detail earlier in this chapter as it pertains to enhancing the benefits of exercise. However, studies indicate that PNF (contract - relax) is an even more effective method of stretching than static stretching, although it is not as widely used. This may be perhaps because little is known about it, it takes more time and requires the skill of a skilled clinician, athletic trainer or strength coach. The details of PNF are many and are beyond the scope of this blog, but the concept is to perform a static stretch for a few seconds, immediately followed by a contraction of the same muscle for an equal amount of time. Upon relaxation of the muscle, then the stretch is taken to the new range of motion and the process is repeated for several repetitions.

Active isolated stretching (AIS) uses the principle of “reciprocal inhibition” which means that in order for the muscle on one side of a joint to contract, the muscle on the opposing side must completely relax. This type of stretching is similar to PNF, but is different in two primary ways: 1., the stretch is deepened by contracting the opposing muscle or muscle group at the same time, and 2., the stretch is sometimes deepened by using a prop or tool such as a block, strap or cord. These two techniques are very common in yoga, which is discussed in more detail below. Different from static stretching, PNF and active isolated stretching are done in shorter time segments, which results in an increase in range of motion with each repetition.

Before a workout or training session is the appropriate time to undertake dynamic stretching. Dynamic stretching should occur just after a period of overall cardiovascular warm up of approximately 5-10 minutes. Dynamic stretching will be covered in detail in the next section, but ultimately involves an increasing warming of the muscles through incremental increases in muscle fiber length gained by rhythmic and repetitive movement through stretching postures.

Another excellent way to increase flexibility and stretch muscles in preparation for exercise or after exercise for recovery is yoga. Many elite athletes today build some sort of yoga into their training routine. There a Yoga, in whatever form you choose, focuses on body awareness, proprioception/balance, core strength and mental focus on both body position and movement patterns, in addition to facilitating muscle, tendon and other connective tissue lengthening and strengthening. With yoga, as is true of many other exercise and stretching methodologies, the style is less important than the frequency and consistency of stretching activities that protect and strengthen the entire body system.

re several types and styles of yoga, varying from meditative styles such as Vinyasa and Iyengar to power styles, such as Flow Yoga and Ashtanga.

Dynamic Stretches

Dynamic stretches are not like traditional static stretches. They are stretches combined with

movement. They are unique in the fact

that they work on flexibility, proprioception, strength and endurance

simultaneously. They are not ballistic and

one should not bounce at the end range of motion. This type of stretching is very effective in

increasing flexibility via a contract – relax methodology, which is used in

both PNF and AIS stretching as well.

When doing dynamic stretches, it is important to keep the following guidelines in mind:

- Dynamic stretches should not cause

pain. Athletes will feel a stretch

throughout the lower kinetic chain but should not experience pain during

or after the stretch.

- If the athlete is too tight to obtain

the optimal position, have him or her move into a range that is

comfortable and progressively keep attempting to move into the ideal

position. The goal is to have the

subject obtain the full range of the motion.

- Participants should perform some warm up

prior to attempting dynamic stretches. We recommended 10-30 minutes of

cardiovascular warm up first.

- Although these are used as a warm up exercise, they are difficult and will result in some muscle soreness. Therefore, a vigilant eye to technique is important to prevent training or retraining of poor motor patterns. If the subject has a difficult time performing the full range of the motion (like step through in dynamic lunge) you can break the movement up into easier components (step through to the opposite foot instead of to the full forward lunge).

Dynamic stretches are an extremely effective tool to increase flexibility as well as lay the foundation for appropriate motor planning when performed correctly. These are also an essential part of the maintenance program that should continue to be a part of any continued conditioning program.

No comments:

Post a Comment